Liquid cooled

- September 25th, 2005, 9:56 PM

- Posted in reviews . technology

- Write comment

So I now have a couple different friends who are swearing by liquid cooling systems for PC cooling needs. I decided to go and do the research for whats available, how much it all costs, and what the options are.

The fruits of that research are here. First, like with just about anything else in the computer hardware purchase universe, there are a wide range of prices, technologies and especially opinions on how to throw things together. Sometimes its hard to distinguish marketing from misrepresented opinions and reality. In my own wading through the murky depths of this topic, I ended up with one particular vendor at the end.

So the basic principle for any cooling mechanism is to find an efficient way to take the inherent heat of your varied chipsets (main CPU, northbridge, and GPU) away from the chip and, preferably, vent it somewhere outside of the case itself. Some of the components in your PC don’t like high ambient temperatures either, so anything you can do to have this excess heat dissipate elsewhere. The more traditional methods for doing this involve heatsinks and fans, most typically. The heatsink is usually a metal set of ‘fins’ with very high surface area that have a clean contact with the surface of the chip in question (this is where all the funny white goop comes in, just make sure the heat exchange is good). Hopefully, with sufficient airflow through the fins, the heat will be taken away with the airflow venting out the back of the system.

The problems with those sorts of systems are numerous, but most have to do with when fans fail. When the airflow is reduced to a sufficiently low level, the heat doesn’t leave the case, and in worst cases, doesn’t leave the chip itself. Components overheat, sometimes fry, and you’re left with metallic slag where your processor should be.

So how does liquid cooling fit in? Well, it works in much the same way that it does with an engine. The hot and heat generating parts are surrounded by tubes filled with liquid, like coolant or water. The water is continually moving. The heat (hopefully) transfers from the hot engine parts to the water. At some point, the water is forced through the radiator, which is filled with metal fins with very high surface area. Air coming through the grill (or being forced to flow over it with a fan) then takes the heat away into the air, the water is cooled again, and the process repeats.

Same principle here. Instead of the normal heatsinks on top of the processors, you have special ones that, while still made of metal, are empty inside, providing a reservoir through which the water or coolant will move. Each of them has an ‘in’ and ‘out’ port that liquid is forced through. Eventually, the liquid reaches either an active cooling radiator, or a larger passive cooling tower, the heat moves into the air, and then the liquid is forced back into the system again.

So a complete liquid cooling system must include several components then. Typically: a pump, a reservoir, a radiator (convection or forced air), tubing, and then the actual ‘interfaces’ to the chips you want to keep cool, sometimes called a ‘cooling block’ or ‘water block’. I’m going to make an attempt to embed some pictures in here of typical elements. Let see if this works. Here’s an example of a water pump (left):

Here’s another view with the water pump attached to a reservoir (right):

The reservoir gives you a way to visually assess how the overall levels of liquid in your system are doing, and refill if necessary. For radiators, there are two types, true convection (passive) radiators and forced air (fan) style. Here are a few images of those.

Convection:

and Forced air style (left):

There are also more traditional ‘fin’ style radiators. Here’s an image of a reservoir and radiator attached to the outside of a case (right):

Finally, we get to the interface elements themselves. Here are a couple examples of CPU liquid blocks (left and right):

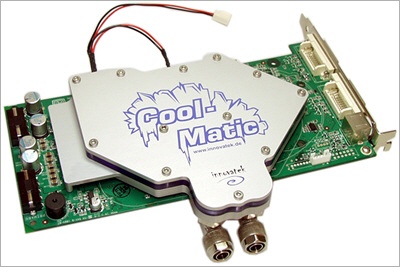

Here’s a great image of one for a video card, and most likely the one I’d get (its for the nVidia 6800, among others) (left):

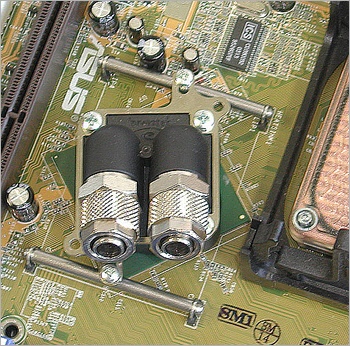

And finally, one of a northbridge cooler block (right):

So, what does this all mean? My basic premise for making a vendor selection was a couple of different criteria. First, that it received decent reviews in sites/reviewers that I already respected. Second, I didn’t want to get a system that wasn’t going to be transferable should I choose to upgrade to a new architecture or system. Fine, I may need to purchase a new actual chip inteface ‘block’ component, but the basic other components should be standard and good enough that a completely new set of gear would be necessary. Price was, at best, a tertiary concern. My personal preference is always to get the best quality, and spend the extra time saving up to do it right the first time. The downside? This ain’t cheap. At first pass, with the components mentioned and shown above, I’m looking at probably about $800 or so, after shipping costs are included. So … Ramen and hot dogs for a few months before I do this.

No comments yet.